Pietro Vesconte is one of the earliest creators of nautical maps, and the first professional cartographer to sign and date his works regularly. This is one of the many contemporary planispheres made by the European clergy. They continue a legacy adopted from the ancient world, and were gradually expanded and adapted in accordance with the texts which they accompanied. The commentaries and learned notes added to the texts formed the basis of further alterations to these maps.

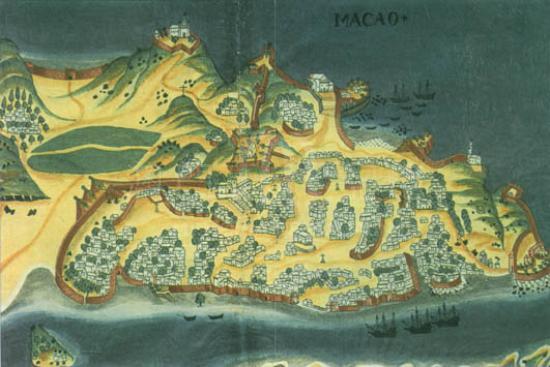

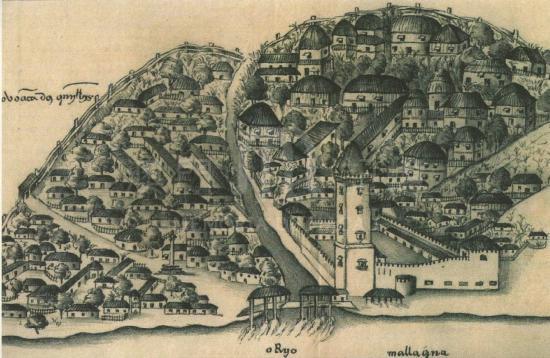

This planisphere is currently bound together with four other maps, some of which are nautical, and one of them is signed by Pietro Vesconte. All five maps are on parchment sheets folded in half, which measure about 30.3 x 47.6cm laying flat. The planisphere has a diameter of about 27cm and is oriented toward the East at the top, showing Jerusalem at the center of the world. The ocean surrounds the known landmass of the world, while the outer parts are largely conjectural. Colors are fairly typical of the medieval period: the oceans, seas and rivers are in green, the saw-tooth mountains in brown, the major cities represented by crowns and castles in red, and the landmasses in white. Of the legends present on the four corners of the planisphere, the two at the top regard Asia; the one at the bottom on the left, Europe; and the one at the bottom on the right, Africa.

In essence, the planisphere is a nautical map of the Mediterranean world, combined with works of previous types in more remote regions. The shorelines of the countries well-known to Italian mariners are very accurately delineated. Chinese and Indian Asia reflect little of the new knowledge gained by European travelers from the time of Marco Polo. As with the previous map, East Asia is represented at the upper left, with descriptions such as 'incipit regnum cathay' (the Kingdom of Cathay begins); 'hic fuerunt inclusi tartari' (here the Tartars were closed).

Reference:

[1]. ALMAGIÀ, R. (1944). Planisferi, carte nautiche e affini dal secolo XIV al XVII esistenti nella Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. In Monumenta cartographica Vaticana (vol. 1, pp. 13-16). Città del Vaticano.

[2]. Scafi, A. (2005). Pio II e la cartografia: un papa e un mappamondo tra Medioevo e Rinascimento. In Enea Silvia Piccolomini, Pius Secundus Poeta Laureatus Pontifex Maximus. Atti del Convegno Internazionale 29 settembre - 1 ottobre 2005, Roma e altri studi, p. 252.

[3]. Campbell, T. (1986). Census of Pre-Sixteenth-Century Portolan Charts. Imago mundi: the Journal of the International Society for the History of Cartography, 38, p. 82.

Informações relevantes

Data de atualização: 2020/09/08

Comentários

Comentários (0 participação(ões), 0 comentário(s)): agradecemos que partilhasse os seus materiais e histórias (dentro de 150 palavras).